Indexes

In 1840 a former soldier, Indian trader, promoter, and Justice of the Peace named Joseph Renshaw Brown set up a small warehouse at the head of Lake St. Croix to supply his upriver fur trading operations. This warehouse, in what is now the north part of Stillwater, became the county seat of St. Croix County, Wisconsin Territory. Brown began building a courthouse and jail and importing settlers for his new village, which he named Dacotah.

Several of Brown’s relatives, including his half-sister Lydia Ann and her husband, Paul Carli, moved into a house built of tamarack logs. The Tamarack House, well known as “Mrs. Carli’s,” became a favorite stopping place for travelers on the St. Croix River. However, few other settlers arrived in Dacotah.

In 1842 Jacob Fisher, former millwright for the St. Croix Falls sawmill, was living in Dacotah. He made a claim to south and diverted Pine (now Browns) Creek through a lake on top of the bluff to provide a water power. Fisher soon sold his claim to John McKusick and three other lumbermen who were looking for a good millsite. The four men formed the Stillwater Lumber Company and had a mill in operation by spring 1844. A few years later, McKusick became the sole owner of the mill.

As word spread of the new mill, settlers began arriving. The John Allen family was the first to settle in the new village of Stillwater. He was followed by Anson Northrup’s family. Northrup built a hotel, which he sold to William Willim, and went on to build another. By 1846 Stillwater had about 10 families and 20 single men; Dacotah was all but abandoned. The Carlis moved to St. Mary in Afton; the courthouse and jail were never finished. In January 1846 Stillwater was made the new seat of St. Croix County.

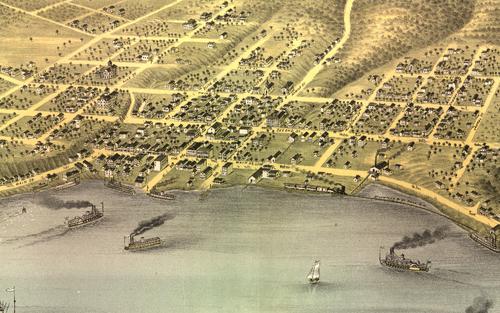

Stillwater was platted in 1848, a town of about 600 people, nearly all lumbermen. When Wisconsin entered the union that year, leaving lands now in Minnesota without government, delegates from the area met in Stillwater. The Stillwater Convention that August appointed Henry Sibley to petition Congress for the early organization of Minnesota Territory. Minnesota became a Territory on March 3, 1849. The first Minnesota Territorial Legislature named the county Washington and confirmed Stillwater as its county seat. On March 4, 1854, Stillwater was incorporated as a city. John McKusick, the man who had named the community for Stillwater, Maine, was elected Stillwater’s first Mayor.

Within a year of Minnesota becoming a territory, the decision was made to locate the territorial prison in Stillwater. The prison was completed by 1853 in Battle Hollow, a natural ravine north of downtown. The ravine got its name from an incident that occurred in July 1839. Both Dakota and Ojibwe parties had visited the Indian Agent at Fort Snelling. There had been a quarrel, and when the Ojibwe party started for home, the Dakota pursued them. The Dakota came upon their enemies encamped in the ravine and fired on them, killing 21. It was rather a one-sided battle, but one of the last confrontations for these two nations.

Stillwater had all the ingredients for a lumbering town: river connections to the northern Minnesota and Wisconsin pine lands, still waters for assembling rafts, and water power. In the 1850s huge steam-powered mills and a log-holding boom were built and Stillwater became the supply depot for the entire St. Croix valley. Early stage roads connected the city to St. Paul, Marine, and Point Douglas.

Railroads arrived in Stillwater in the early 1870s, vastly expanding markets for timber and manufactured goods. The first rail line, a branch line of the Mississippi & Lake Superior (now the Northern Pacific) from White Bear Lake, entered town from the north. The second, the St. Paul, Stillwater & Taylor’s Falls (now the Omaha Road) came from the south. Soon the city was connected to Chicago through the Milwaukee road (via Lakeland and Hastings) and in the 1880s via the Soo line. As the sites near the rivers were logged out, logs began arriving in Stillwater via rail. Manufactured products ranging from lumber and shingles, windows and doors, furniture and flooring, to farm machinery, steam engines, and rail cars—as well as grain, feed, and flour from the elevators—were shipped to customers in Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, and Dakota Territory via rail.

Stillwater entered a golden age that produced the grand homes of the lumber barons, the biggest opera house west of Chicago, and many magnificent brick buildings on Main Street. It had gas lights in 1875, telephone service downtown in 1878, and the first electric lights west of Chicago in 1888. The city also boasted as many as 46 saloons and was home to six breweries. In June 1889, the first electric street railway in Minnesota began operation in Stillwater.

By 1900 the lumber was giving out and the mills closed. The final failure of the largest manufacturer, the Minnesota Thresher Company, in 1914 coincided with the last lumber rafts leaving Lake St. Croix and the moving of the state prison to South Stillwater, and began Stillwater’s rapid population decline as workers moved away. However, the diversity of business in Stillwater prevented it from becoming a ghost town. The Muller boat works, Connolly Shoe Company, Simonet Furniture Company, farm equipment makers, flour mills, and elevators kept operating. The Twin City Forge & Foundry survived by building barges and making munitions and shell casings.

As the jobs left, Stillwater’s population declined from a high of more than 13,000 in the 1880s to a low of around 7,000 in 1940. The Forge closed in 1930; the Omaha took out its tracks in 1935. However, the population began to recover after World War II when good roads and automobiles put residents in commuting range of the Twin Cities. In the 1970s the first planned residential developments were built west of downtown and a “strip” of businesses appeared flanking Highway 36. Stillwater began to reinvent itself as a tourist destination. Fabulous old mansions got new life as bed and breakfasts. Old waterfront buildings were torn down (some regrettably) and others were reused. Restaurants were installed in the beer caves and freight house, shops in the old utility buildings and mills, and a hotel in the old Lumberman’s Exchange. In its third century, Stillwater is a bustling community boasting a variety of industry and business from automotive and plastics technology to government, banking, and medical services.

Stillwater became a city in 1854. At that time it was the largest incorporated area in the state. By 1857 the population was 2,800, soaring to 13,700 by 1884. As the lumber industry gave out, Stillwater lost population until it bottomed at around 7,000 in 1940. Suburbanization gave the city new life, and by 1980 Stillwater had regained her historic population of 13,000; in 2006 the number of residents had risen to 17,900.

Historic Sites in Stillwater

- Albert Lammers House

- Boutwell Cemetery

- Capt. Austin Jenks House

- Fairview Cemetery

- Freight House Restaurant

- Ivory & Sophia McKusick House

- Mortimer Webster House 1021 3rd St S

- Mortimer Webster House 437 Broadway St. S

- Nelson School

- Pest House

- Phil’s Tara Hideaway

- Pine Point County Farm Cemetery

- Roscoe Hersey House

- Salem Lutheran Cemetery

- St. Croix Boom Company House and Barn

- St. Croix Boom Site

- Stillwater Commercial Historic District

- Stillwater Interstate Lift Bridge

- St. John’s Lutheran Church of Baytown Cemetery

- Stone Bridge

- Warden’s House

- Washington County Historic Courthouse

- William Sauntry Mansion

Relevant Online Indexes

- 1881 Washington County History

- 1896-97 Stillwater City Directory

- 1898-99 Stillwater City Directory

- 1901 Northwest Pub. Plat Book

- 1902-03 Stillwater City Directory

- Boutwell Cemetery

- Fairview Cemetery

- Fairview Cemetery sexton books

- First Presbyterian, Stillwater, 1874

- Names in WCHS Scrapbook Index

- Peterson’s Stillwater City Directory Death Listings

- Polk’s Dual City Business Directory 1889-90

- Polk’s Stillwater City Directory 1890-91

- Poor Farm deaths compiled by WCHS

- Poor Farm Register, Volume 1

- Reconstructed prisoner list

- Register of Deaths, Stillwater, Book A, 1884-1899

- Registration of Alien Ememies, Stillwater area, 1918

- Rutherford Cemetery

- Salem Lutheran Cemetery

- Small, lost and abandoned cemeteries

- Stillwater Arrest Records 1907-1925

- Stillwater births, April 1897 – December 1899

- Stillwater City Directory 1876-1877

- Stillwater City Directory 1890-1891

- Stillwater City Directory 1900-1901

- Stillwater City Directory 1930-1931

- Stillwater Deaths 11/19 /1929 to 11/26/1930

- Stillwater Deaths 6/1902-8/1905

- Stillwater Gazette Photo Collection

- Stillwater High School graduates, 1876-1899

- Stillwater High School Record of Daily Work 1902-03

- Stillwater High School Record of Daily Work 1916-1917

- Stillwater Police Register of Arrests, 1878-1882

- Stillwater Police Register of Arrests, 1882-1898

- Stillwater Soft Drink Licenses

- St. John’s Lutheran Church of Baytown Cemetery

- St. Michael’s Church Pipe Organ Donors, early 1900s

- St. Paulus Evangelical Lutheran, Stillwater, 1897

- St Paulus Ev Lutheran Gemeindeglieder, c 1881

- Tramps Lodged – not committed in Stillwater 1907-1925

- Washington County in the World War, 1917-1918-1919

- Washington School Class Photos

- WCHS Biographic Files

- WCHS Deeds

- WCHS Photograph Collection

- WCHS School Scrapbook